You are one of the first cruise catamaran architects in France. Can you remind us of the context of the emergence of the multihull in French yachting?

In the 1980s, there was no cruise catamaran built in France. You could see boats built in the UK like the Snowgoose, Quest, Catalac, Iroquois or SailCraft Comanche. There was also the Catfisher, a kind of trawler on two hulls, closer to a fifty than a high-performance sailboat. Less known in France, Australians like Lock Crowther also developed some models of catamarans for cruising.

It was at this time that I arrived at Philippe Harlé, with a draft catamaran in my boxes. But the goal, unlike the English models, was to take advantage of catamarans to make high-performance sailing boats. At first, he wasn't too keen. It seems that Marc Lombard, who had passed before me had already tried to convince him, without success. I finally made up my mind. Thus was born the Punch 8.50, a plywood catamaran that easily reached 15 knots in a ballad-camping configuration. In parallel, we have developed with the Benedictine small sports catamarans not too expensive, the Jet 27 and Jet 31, names in phase with Philippe Harlé's link with the world of spirits !

It was in those years that Fountaine launched the Louisiana, a catamaran, also dedicated to fast cruising. When it arrived in France, the catamaran was clearly performance-oriented.

What changes did you see in the multihull architecture in the 1990s/2000?

The evolution towards more livable boats for cruising has led to the development of the platforms. This obviously led to weight gain. And this overweight has been to the detriment of the marine capabilities of cruising catamarans. It was necessary to increase the volume of the floats, to arrive at hulls in"ping-pong ball". Flat on the bottom, they are more habitable but the passage in the sea is much less good. On our side, when we designed the Punch 1000 and the first Nautitech, we tried to limit the race to the equipment to keep the boats light and the floats narrow enough, thus protecting the crew from fatigue.

With tax exemption and rental, catamarans quickly became synonymous with coconut palms and warm seas. In the tradewinds, even with a little weight, we still walk. The important thing has become to enjoy the space. So with the first Nautitech, we were able to work on the layout on the ground floor. This is one of the catamaran's other advances, which makes it possible to live more comfortably on a single deck.

And today what changes do you see in the multihull market?

Since the 1990s, we have not stopped growing, which has created a void in the field of boats dedicated to performance. What made the catamarans grow is the holidays and not the trip. Indeed, sailing ships like the Overseas Territories, which were dedicated to travel, remained rather efficient. We see today with the arrival of new top-of-the-range boats, very light as the Banuls or Alibi present on the show, that there is a renewal of the fast catamaran. With the evolution of the way of life, people who have money do not have time for a long trip, but they seek sensations. New materials design and processing technologies are creating new boats to meet this demand.

On your side, what are your multihull projects and desires?

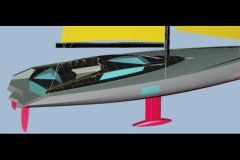

In terms of project, I work with the Alubat shipyard at OvniCat 48, an aluminium travel catamaran. It is an interesting material for travel and you can stay in weights comparable to resin boats.

For the desires, I obviously have some, which will come true or not. I would like to have the opportunity to design an original boat that comes out of what we see on this show...